The British Raid

The British Raid

on the

American Naval Base at

Sacket’s Harbor, 1813

When the campaign season opened in April 1813, the United States planned to exploit their control of Lake Ontario by attacking Kingston, York and Fort George in the Niagara, with a force assembled at Sackets Harbor. As American intelligence indicated the defences at Kingston were formidable, it was decided to first attack York and then hold it until a relief force was detached from Fort George to reclaim it. The Americans would then make a lightening move across Lake Ontario, reduce that fort and, aided by an army that would cross the river, secure the Canadian side of the Niagara. Afterwards, a blockade was to be established at Kingston to contain the British naval squadron. American Commodore Chauncey would then proceed direct to Lake Erie and then “destroy” British naval power, take Malden and Detroit, and then proceed into Lake Huron and attack Mackinac.

The enemy object at York was to destroy naval stores and weaken British naval strength by capturing two brigs under construction at the dockyard and the schooners Prince Regent and Duke of Gloucester. The attack on York would demonstrate the growing American amphibious capabilities, which in this case allowed them to transport 1,700 men, under the overall command of Major-General Henry Dearborn, across Lake Ontario. At York, Major-General Robert Sheaffe could only muster 413 regulars, 477 militiamen, 50 native warriors and about 100 miscellaneous personnel, while the town’s main defences included a fort, four battery positions and several unarmed works.

The enemy object at York was to destroy naval stores and weaken British naval strength by capturing two brigs under construction at the dockyard and the schooners Prince Regent and Duke of Gloucester. The attack on York would demonstrate the growing American amphibious capabilities, which in this case allowed them to transport 1,700 men, under the overall command of Major-General Henry Dearborn, across Lake Ontario. At York, Major-General Robert Sheaffe could only muster 413 regulars, 477 militiamen, 50 native warriors and about 100 miscellaneous personnel, while the town’s main defences included a fort, four battery positions and several unarmed works.

During the morning of 27 April 1813, the Americans commenced landing troops to the west of the town. A detachment of regulars, militia and natives sent to meet them was delayed in reaching the landing site, forcing Sheaffe to commit his reserve to support the native warriors who were engaging the enemy. Superior numbers and fire support from Chauncey’s squadron overwhelmed the defenders, who began to withdraw to York. By the time he reached Fort York, Sheaffe realized the battle was lost and ordered the Brock and the naval supplies burned and then prepared to withdraw to Kingston, leaving the militia to surrender the town. In addition, he ordered the grand magazine at Fort York to be detonated, which occurred just as the Americans approached the fort. The debris from the explosion caused 250 casualties amongst the enemy. Contrary winds and poor weather forced Dearborn and Chauncey to remain at York for several days and once they left, fatigue and sickness had weakened their men so much that Dearborn cancelled plans for a direct assault on Fort George, and the squadron returned to Sackets Harbor to rest and refit.

During the morning of 27 April 1813, the Americans commenced landing troops to the west of the town. A detachment of regulars, militia and natives sent to meet them was delayed in reaching the landing site, forcing Sheaffe to commit his reserve to support the native warriors who were engaging the enemy. Superior numbers and fire support from Chauncey’s squadron overwhelmed the defenders, who began to withdraw to York. By the time he reached Fort York, Sheaffe realized the battle was lost and ordered the Brock and the naval supplies burned and then prepared to withdraw to Kingston, leaving the militia to surrender the town. In addition, he ordered the grand magazine at Fort York to be detonated, which occurred just as the Americans approached the fort. The debris from the explosion caused 250 casualties amongst the enemy. Contrary winds and poor weather forced Dearborn and Chauncey to remain at York for several days and once they left, fatigue and sickness had weakened their men so much that Dearborn cancelled plans for a direct assault on Fort George, and the squadron returned to Sackets Harbor to rest and refit.

The enemy then struck again and, on 27 May1813, following a two-day bombardment of Fort George, an American army landed in the Niagara Peninsula. Their objective was to encircle and capture British forces near Fort George, but Brigadier-General John Vincent, commanding in the Niagara region, implemented a contingency plan to withdraw his command to the safety of Burlington Heights. The following day 3,000 enemy soldiers, set out in pursuit. Heavily outnumbered, and with Chauncey commanding Lake Ontario, the British found themselves in a difficult situation.

The enemy then struck again and, on 27 May1813, following a two-day bombardment of Fort George, an American army landed in the Niagara Peninsula. Their objective was to encircle and capture British forces near Fort George, but Brigadier-General John Vincent, commanding in the Niagara region, implemented a contingency plan to withdraw his command to the safety of Burlington Heights. The following day 3,000 enemy soldiers, set out in pursuit. Heavily outnumbered, and with Chauncey commanding Lake Ontario, the British found themselves in a difficult situation.

Sir George Prevost was in Kingston where, on 26 May, after learning that Fort George was under a tremendous bombardment that began on the previous day, he concluded this was a prelude to an enemy assault on the fort and proposed a bold plan to relieve pressure in the Niagara and to divert American attention—he would attack the enemy naval base at Sackets Harbor. Prevost first conceived this idea on 22 May, when an American spy confirmed that Chauncey’s squadron was at the western end of the lake. Yeo conducted a reconnaissance of Sackets Harbor during the night of 26 May that confirmed that Chauncey’s squadron was absent and that the garrison appeared to be weak. Prevost appointed Colonel Edward Baynes to command the raid and began planning in earnest. During 27 May, units were mustered, and the squadron readied for departure.

Sir George Prevost was in Kingston where, on 26 May, after learning that Fort George was under a tremendous bombardment that began on the previous day, he concluded this was a prelude to an enemy assault on the fort and proposed a bold plan to relieve pressure in the Niagara and to divert American attention—he would attack the enemy naval base at Sackets Harbor. Prevost first conceived this idea on 22 May, when an American spy confirmed that Chauncey’s squadron was at the western end of the lake. Yeo conducted a reconnaissance of Sackets Harbor during the night of 26 May that confirmed that Chauncey’s squadron was absent and that the garrison appeared to be weak. Prevost appointed Colonel Edward Baynes to command the raid and began planning in earnest. During 27 May, units were mustered, and the squadron readied for departure.

The decision to mount a joint attack against an enemy naval base while the American squadron was still on the lake in strength was a risky venture. There were many unknowns. Yeo’s officers and men were about to sail on Lake Ontario for the first time and knew little of the nautical conditions or the handling of their ships. Few details were known about the enemy strength and nobody in Kingston was aware that they would be facing 1,500 American defenders, about twice the strength of the British attacking force.

The decision to mount a joint attack against an enemy naval base while the American squadron was still on the lake in strength was a risky venture. There were many unknowns. Yeo’s officers and men were about to sail on Lake Ontario for the first time and knew little of the nautical conditions or the handling of their ships. Few details were known about the enemy strength and nobody in Kingston was aware that they would be facing 1,500 American defenders, about twice the strength of the British attacking force.

The 900-strong assault force was drawn from the light companies of eight different regiments and included two field artillery pieces and 40 warriors. Less than one-third of the regular troops had seen any action at all. Yeo’s squadron included 800 sailors distributed between five ships, a merchantman, 33 bateaux, three gunboats and several canoes, with his warships mounting a total of eighty-two guns. With only a single civilian transport to carry part of the infantry and the two field guns, most of the soldiers were crowded on the open decks of the warships, leaving little room for the crews to do their work and the extra load carried on each vessel affected its handling. An unfortunate few were also carried in the bateaux, which were towed behind the ships, for the 36-mile journey.

The 900-strong assault force was drawn from the light companies of eight different regiments and included two field artillery pieces and 40 warriors. Less than one-third of the regular troops had seen any action at all. Yeo’s squadron included 800 sailors distributed between five ships, a merchantman, 33 bateaux, three gunboats and several canoes, with his warships mounting a total of eighty-two guns. With only a single civilian transport to carry part of the infantry and the two field guns, most of the soldiers were crowded on the open decks of the warships, leaving little room for the crews to do their work and the extra load carried on each vessel affected its handling. An unfortunate few were also carried in the bateaux, which were towed behind the ships, for the 36-mile journey.

The squadron got underway at night of 27 May and made good progress until early the next morning when the wind died. During the night, an American schooner and spotted the squadron, fired a shot to warn the garrison at the Harbor before returning to base. By 4:30 A.M. on 28 May, the squadron was about 10 miles away. At dawn, Captain Andrew Gray made another reconnaissance and his report offered the welcome news that the American base appeared weakly defended. An hour later the flotilla was still seven miles from its objective when the wind faltered. Yeo then decided to make a personal reconnaissance and when he returned at 3:00 P.M., he and Baynes agreed to call off the attack, and the squadron turned back to Kingston. Shortly thereafter, the wind shifted against the British again. Then, a detachment of 37 natives and several regulars that had been sent out from the squadron in three canoes and a gunboat captured 115 American reinforcements on route to Sackets Harbor. Elated, Baynes and the other senior officers now decided that the ease by which 15 boats from the American convoy had been captured meant that there were poor quality troops at Sackets Harbor. It was agreed to continue with the attack.

The squadron got underway at night of 27 May and made good progress until early the next morning when the wind died. During the night, an American schooner and spotted the squadron, fired a shot to warn the garrison at the Harbor before returning to base. By 4:30 A.M. on 28 May, the squadron was about 10 miles away. At dawn, Captain Andrew Gray made another reconnaissance and his report offered the welcome news that the American base appeared weakly defended. An hour later the flotilla was still seven miles from its objective when the wind faltered. Yeo then decided to make a personal reconnaissance and when he returned at 3:00 P.M., he and Baynes agreed to call off the attack, and the squadron turned back to Kingston. Shortly thereafter, the wind shifted against the British again. Then, a detachment of 37 natives and several regulars that had been sent out from the squadron in three canoes and a gunboat captured 115 American reinforcements on route to Sackets Harbor. Elated, Baynes and the other senior officers now decided that the ease by which 15 boats from the American convoy had been captured meant that there were poor quality troops at Sackets Harbor. It was agreed to continue with the attack.

The decision to proceed with the raid came late in the day of 28 May and as the squadron was still some distance from the proposed landing site, they were forced to remain off the Harbor that night. Several participants claimed that this added delay allowed the Americans time to muster the militia and occupy their defensive positions; which might have been avoided had an immediate assault been acted upon. This is not true. Had the landings been conducted on the late evening of 28 May, the attackers would have still found the defenders already in position and having the coming darkness in their favour.

The decision to proceed with the raid came late in the day of 28 May and as the squadron was still some distance from the proposed landing site, they were forced to remain off the Harbor that night. Several participants claimed that this added delay allowed the Americans time to muster the militia and occupy their defensive positions; which might have been avoided had an immediate assault been acted upon. This is not true. Had the landings been conducted on the late evening of 28 May, the attackers would have still found the defenders already in position and having the coming darkness in their favour.

The defences of Sackets Harbor were considerable. Colonel Alexander Macomb, the officer who commanded the garrison, had correctly anticipated the British would avoid a direct descent as the approaches were well covered by the guns of two forts. Instead, they would establish a foothold on Horse Island about a mile west, cross a narrow channel to the mainland and then advance towards the village. Even if the British overwhelmed the defenders on Horse Island, they would still have to negotiate a massive obstacle constructed from hundreds of felled trees, known as an abatis, that encircled the town and dockyard. If the abatis was penetrated, the British would then face the main American defences, centered on two log barracks. Here a force of regular soldiers, equivalent in number to the entire British assault force, were expected to defeat any attack. Behind them was Fort Tompkins, armed with a powerful 32-pounder gun; farther beyond that, in the low ground, was Navy Point, covered by six guns ranging from 12- to 32-pounders. Overlooking the harbour from the high ground to the east was Fort Volunteer armed with six or seven guns. Altogether the strength of the defenders amounted to 1,500 men and 16 or 17 pieces of ordnance, which outnumbered the attacker’s ground force and enjoyed an eight-to-one advantage in artillery. If their plans fell awry, the Americans were prepared to destroy the naval warehouses and their ship rather than let them to fall to the British.

The British commenced their landings on the morning of 29 May. Baynes then divided his force into two groups. One column under Colonel Robert Young advanced towards the naval dockyard using the shore road, and a second group under Major William Drummond (who had received a light wound during the landing) took a route further inland, to the right of Young. The two artillery pieces that had been brought could not be unloaded, so artillery support was limited to fire from the gunboats and HMS Beresford, whose captain ordered the use of sweeps to row his vessel into the inlet.

About an hour later, the two columns reunited with Young on the left, Drummond on the right. Before them were three barracks buildings. Baynes ordered “an impromptu attack” against the barracks, but it was beaten back “with heavy loss.” Thereafter, Colonel Young, who had been ill when he embarked at Kingston, was unable to continue and returned to the landing site. Major Drummond then suffered a second wound, but continued leading his element. By this point, the supporting fire from the British gunboats ended, as it was masked by a rise in the ground. Baynes was now in a difficult position: he faced a strong, entrenched enemy with clear fields of fire and artillery support, while his infantry was in the open with no artillery support and his force had been reduced to some 300 men.

Prevost now intervened and ordered a second attack. The right of the British line faced overwhelming fire and was rebuffed, but the troops on the left cleared one of the barrack buildings. An attempt to cross the open space to the next barracks was met by heavy fire and more casualties were suffered. Among the wounded were two senior officers, Major Robert Moodie of the 104th and Major Thomas Evans, commanding the companies from the 8th Foot. Another key officer, Captain Andrew Gray, the Acting Deputy Quartermaster General for Upper and Lower Canada, who had helped plan the landings, was killed. Major William Drummond took a message to the Americans demanding their surrender, which was refused. Uncertain what to do next, Baynes consulted Prevost, who ordered the force to withdraw and re-embark.

By this point, the British attack force had been ashore for five hours and while they had advanced inland over 1,200 yards nearly unmolested and were now at the last obstacle before the dockyard, this progress proved deceptive. Approximately 30% of the infantry were casualties and three of the key officers were unable to continue. The attackers were unable to break through the main defensive position, where the protected defenders enjoyed artillery support. Many soldiers were running around aimlessly, and the situation seemed confused as some witnesses believed the columns of dust near the village signalled the approach of enemy reinforcements.

At this critical moment, Prevost directed his attention back towards the stationary British squadron and of where the American fleet might be. If Chauncey’s squadron arrived, the combined British force might be captured in its entirety or intercepted as it returned to Kingston. In a possible naval engagement, the British squadron would have difficulty manoeuvring against the trimmed enemy vessels as the British decks would have been filled with soldiers and equipment. At no time did Yeo, however, express any concern. Rather, he left his squadron, went ashore and was seen “running in front of and with our men … cheering our men on.” The result was that most of the squadron—and its powerful guns—remained out of the battle, and the only British vessels to participate in the battle were gunboats armed with a single 24-pounder carronade each and the 12-gun schooner Beresford. Prevost’s fears of a sudden appearance by Chauncey were never realized—in fact, the American commodore did not learn of the raid until May 30. He departed from the Niagara on the morning of the May 31 and when he returned, decided to remain in Sackets Harbor to await the completion of the Pike, which would give him command of the Lake, but the new ship would not be ready until mid-July, giving Yeo control of the lake for two months.

While historians have strongly criticized Prevost, for ordering the withdrawal, the essential truth is that the Americans had anticipated where the British would land and had prepared their defences accordingly. They developed an effective, layered defense that used obstacles to wear down the British. The struggle reached a crescendo at the main American position at the cantonment, where the buildings aided the defenders. The final British assault was unsupported. There is no real evidence that success could have been achieved had the attack continued and every reason to believe that British casualties would have increased. The raid was one of the most-costly actions the British conducted in the northern theatre and the casualties suffered were greater than those at Queenston Heights, York, Stoney Creek, Chateauguay and Crysler’s Farm.

One key outcome of the raid on Sackets Harbor is undisputed—this was Chauncey’s decision, following the attack, to withdraw naval support for the American army at the Head of Lake Ontario and then to remain in port to protect his new ship. This decision was a major turning point of the war as control of Lake Ontario, which had been held with such advantage by Chauncey since November 1812, now passed to Yeo. Prevost immediately exploited this turn of events by sending the commodore to deliver reinforcements along with much-needed supplies to Vincent’s army at Burlington Bay. Meanwhile, Vincent approved of a plan to attack the American camp at nearby Stoney Creek. During a night action on 5/6 June 1813, 700 British troops confronted over 3,000 Americans, captured their two generals and left the defenders in disarray. On 7 June, the Americans withdrew eastwards to 40 Mile Creek. By this time, Yeo had worked out a plan with Vincent to cut off the American force, but Dearborn, the American commander at Fort George, fearing this might occur, ordered it to withdraw to Fort George. By the second week of June, all American forces were back at Fort George and remained there for the summer. Encouraged by these successes, Yeo next ranged around Lake Ontario, ferrying troops, bombarding shore targets, landing raiding parties and even preparing another assault on Sackets Harbor—which was cancelled once surprise was lost—before anchoring off Kingston at the end of June.

The British raid on Sackets Harbor may have been a tactical failure, however, it reaped operational benefits that undid American plans in the spring of 1813.

Crown Forces Killed at the Second Battle of Sackets Harbor, 29 May 1813

Royal Navy

AB Alexander West

1st Battalion, 1st (The Royal Scots) Regiment of Foot

Pte William Doubtfire

Pte Thomas Mulvaney

8th (The King’s) Regiment of Foot

Pte Samuel Curtis

Pte John Patterson

Pte Richard Pearson

100th (His Royal Highness the Prince Regent’s County of Dublin) Regiment of Foot

Sgt T William McGarry

Pte John Carvin

Pte Michael O’Brian

Pte John Short

Pte Michael Quinn

Pte James Murphy

104th Regiment of Foot

Sgt Hugh McLaughlan

Sgt William Sands

Cpl William Ward

Pte David Antwerth

Pte Colin Connell

Pte George Curli

Pte Joseph De Route

Pte Louis Des Jardins

Pte Stephen Geary

Pte Robert Gibson

Pte Louis Goudreau

Pte James Hayward

Pte John Heneberry

Pte Francis Jandron

Pte Charlemagne Le Vasseur

Pte James McKay

Pte Bartholomew Parenteau

Pte Noah Phelps

Pte Robert White

Pte Timothy Woodward

Royal Newfoundland Fencible Infantry

Pte CT Detzer

Pte Nicolas Dupene

Pte Henry Emberly

Pte John Lefsted

Pte George Kelly

Pte John Wilcox

Nova Scotia Fencible Infantry

Capt Andrew Gray (on staff)

Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles

Pte Ebenezer Buck

Pte John Carrol

Pte John Hilliman

Pte Malcolm Stewart

Pte James Thompson

Pte John Tournelle

Provincial Corps of Light Infantry (Voltigeurs Canadiens)

Soldat Augustine St. Germain

Soldat John Maid

Sackets Harbor NY

Graveside Project Plaque Placement

Aug. 5, 2017 Plaque placement in front of the 1804 Ontario Masonic Lodge, Union Hotel, Main St. Sackets Harbor, New York U.S.A..

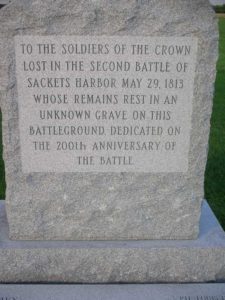

The Canadian Graveside Project Plaque was placed to honour the 47 Crown Forces soldiers killed in the second battle of Sackets Harbor May 29, 1813.

The unveiling of the plaque was carried out by Rev. Canon Roger Young 4th Gr. Grandson and David Aldus 3rd Gr Grandson of Capt. William Brown Bradley of the 104th Regiment of Foot who participated in this battle.

Derek Browning M.C. read the names and regiments of the 47 men lost in the battle followed by the plaque unveiling and the dedication ceremony.

Application Credit

David Aldus

Photo Credits

David Aldus

Keith Hobbs

Professor Bruce Elliott

Excerpt Credit

The British raid on the American Naval Base at Sackets Harbor 1813.

The 104th Regiment of Foot in the War of 1812 as prepared by the Author John R Grodenski. Assistant Professor of History at the Royal Military College, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Special thanks to the Mayor of Sacket’s Harbor and to Barone, Constance (Parks) for coordination the event.

Special thanks also to both the American and Canadian re-enactors and all who assisted in the event and plaque placement.

Veteran Summary

Crown ForcesVarious, Crown Forces

Place of Birth

Various, Various, Various

Place of Death

Sackets Harbor, Jefferson County, NY, USA

Died on: 29 MAY 1813

Reason: Battle

Location of Grave

Union Hotel, Main Street

Sackets Harbor, NY, USA

Latitude: 43.948627N Longitude: -76.122964